- Home

- Brett Dakin

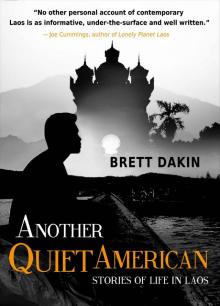

Another Quiet American

Another Quiet American Read online

Praise for Another Quiet American

____________________

“No other personal account of contemporary Laos is as informative, under-the-surface and well written.”

-- Joe Cummings, author of Lonely Planet Laos

“A must for anyone looking to understand Laos today.”

-- Jeff Cranmer, author of Rough Guide Laos

“A witty, personal account ... through the eyes of a young American among raucous expats in Vientiane.”

-- Frommers Southeast Asia

“An excellent contribution to a better understanding of life in Asia.”

-- Far Eastern Economic Review

“Honest, well written, entertaining and informative.”

-- South China Morning Post

“A delightful insight into one of the forgotten nations of Southeast Asia.”

-- Metro magazine

“A fascinating account, full of sharp insights about a country at a turning point in its history.”

-- Bangkok Post

“A thought provoking book... Dakin writes with a maturity well beyond his years... An excellent book...”

-- Lang Reid, Pattaya Mail

“An intimate and honest look at the genteel chaos of a country that is deeply troubled but also highly inspiring.”

-- Amit Gilboa, author of Off The Rails In Phnom Penh

“Probably the best introduction available on modern Vientiane.”

-- Farang Magazine

Another Quiet American

Stories of Life in Laos

__________________________________

BRETT DAKIN

Contents

__________

Introduction to the Fifth Edition

Author’s Note

Part I

Remembering

The General

Lent’s Over

The Prince

My Honda Dream

The Game

Revelations

Funny Money

The Consultants

Another Quiet American

Vive la France

Protest

War

Part II

Amarillo

Up North

Lonely in Laos

That Luang

Sugar Daddy

For the Birds

The Lost Generation

Across the River

Alone

Party Time

Thank You Very Much

Forgetting

About the Author

Copyright

Introduction to the Fifth Edition

Sometimes one wonders why one bothers to travel, to come eight thousand miles to find only Vientiane at the end of the road.

Graham Greene

During a visit to Indochina in January 1954, the English novelist Graham Greene made a brief stop in Vientiane. He was not impressed. In his diary, Greene described the Lao capital as “an uninteresting town consisting only of two real streets, one European restaurant, a club, the usual grubby market where apart from food there is only the debris of civilization—withered tubes of toothpaste, shop-soiled soaps, pots and pans from the Bon Marché.”

When I showed up in Vientiane nearly a half-century later, in the autumn of 1998, to work at the National Tourism Authority of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, not much had changed. The airport consisted of a single small building; local farmers freely crossed the crumbling runway with buffalo in tow. Mobile phones were very rare, Internet access reserved for the privileged few (and extremely patient). Foreign tourists were scarce, as the government had only recently begun to allow visitors to easily enter the country. The central Morning Market was still about the only place where people shopped; for anything other than the “debris of civilization,” the better-off made a run for the border and crossed into Thailand. Greene had complained about the dearth of offerings at the local movie house, but when I arrived there was not a single working cinema in the entire country.

While the sleepiness of the Lao capital had bored Greene (“Vientiane is a century away from Saigon,” he wrote, with derision), to me it was a revelation. The absence of the trappings of modernity, so unique among the world’s capitals at the century’s end, along with the intimacy it afforded—this was precisely what I found interesting about Vientiane, and what prompted me to write about the city and its diverse inhabitants. Where else in the world could one live across the street from an ancient Buddhist temple, where one’s landlord’s ancestors were buried, and awake at dawn to the sounds of the steady beat of the monks’ drumming? Teach conversational English to the richest man in the country and, after work, study French with the Polish ambassador? Dine in style with the president’s daughter, then share a beer with a neighbor whose livelihood depended on his chickens’ productivity? Unlike Greene, I knew why I had bothered to travel across the world to Vientiane.

As the first decade of the twenty-first century draws to a close, Vientiane is no longer a century away from Saigon—or even New York, where I now live. I have just returned from a visit to the city, on the verge of celebrating the 450th anniversary of its establishment as the nation’s capital. Money now flows through the streets of Vientiane—and not simply development aid from the West. There is real investment taking place, especially from Laos’ neighbors in the region. When I lived in Laos there was not more than a handful of traffic lights in the country; there is now one every few blocks in Vientiane. Back in the saddle of a motorbike after so many years, I marveled at the phenomenon of rush-hour traffic as I weaved my way through the lines of hulking SUVs. I often became hopelessly lost: entire neighborhoods have popped up in areas where a few years ago there were rice fields. Friends, Lao and expatriate alike, now document every moment of their lives and connect with the wider world through Facebook. And tourism has boomed. I stopped by the NTA to pick up a copy of the latest report from the Statistics Unit, which an old colleague now runs, and the official numbers told the story: two million tourists visited Laos in 2009, four times as many as had made the trip in 1998, the year I arrived.

The era in Vientiane’s history that is captured in the pages of this book has passed. In some ways, that is certainly a good thing; in others, I must admit, I am not so sure. Ultimately, beneath its newly polished surface, Vientiane continues to struggle with many of the same problems I documented a decade ago—challenges that are more urgent now than ever.

___

The shiny gold lettering on the invitation indicated the dress code for the evening: Lounge Suit/National Dress. Hoping that the one business suit I had packed would pass muster under either category, I tucked my trousers into my socks, hopped onto my rented Suzuki, and drove over to the Prime Minister’s Office. Before I could reach the front gates of the massive new complex, which dwarfed the building that had until recently served the same purpose, I was stopped by two policemen busily directing traffic. In response to my pleas to enter, the officers only blew their whistles. I watched for a moment as black limousines deposited dignitaries like the princess of Belgium at the grand entrance, just opposite Patuxay, Vientiane’s Arc de Triomphe, then drove quietly around to the back gate. I parked, dusted off my suit, untucked my pants, and walked past the newly-laid turf, portable toilet units, and temporary kitchen tents filled with workers to the front of the building. There I joined the parade of international guests striding down the red carpet towards their tables for this Gala Dinner under the stars.

The occasion for the glittering event, and my visit to Vientiane, was the First Meeting of States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, a new international treaty banning the very weapon that the U.S. had used in Laos during the Vietnam War and which con

tinues to devastate the country today. It was fitting that Laos, one of the first countries to sign the treaty, was hosting the meeting: the U.S. bombing campaign from 1964 to 1973 had left millions of unexploded cluster submunitions in the country, affecting 25% of all villages. Nearly four decades after the war ended, children in Laos are still being injured and even killed by these weapons on a regular basis. More than 110 governments had sent representatives to the Vientiane meeting, as well as UN agencies, international organizations and a host of non-governmental organizations. Among the attendees were many persons with disabilities, prompting the organizers to work with hotels and other facilities around town to ensure accessibility. This was the largest such meeting Laos had ever hosted—a feat impossible to imagine when I had lived there—and the government was determined to put on a good show.

I spotted the interim U.S. ambassador, in attendance at the dinner despite his government’s failure to accede to the treaty, and joined him for a few moments in the VIP section. Tuxedoed waiters in white gloves served platters of food catered by the Lao Plaza Hotel, where I had done my weekly aerobics years before. The items listed on the printed menus at each place, including braised shark’s fin and Roasted Duck Hong Kong, reminded me of the ever increasing Chinese influence in Lao affairs. The rest of us, thankfully, were free to graze at the buffet serving good old-fashioned Lao standards like white and purple sticky rice, succulent grilled chicken, and rice noodles in curry soup. On stage, a festive performance organized by the Ministry of Information and Culture was well under way. In between bites, I caught glimpses of young men and women in traditional Lao dress dancing in formation to familiar national tunes. A fashion show celebrated the costumes of each of Laos’ officially recognized ethnic minority groups. As this was the first time most of the invitees had ever visited Laos—the two diminutive delegates from Albania, dressed in diplomatic grey, seemed particularly enthralled—it was a great opportunity to showcase the country’s culture.

After dessert, the final performance was announced: a piece by “Michael.” A pair of young Lao pop stars, one in a black suit, the other a long red gown, strode onto the stage, wireless microphones in hand, and belted out the opening lyrics, familiar to all in attendance:

There comes a time

When we heed a certain call

When the world must come together as one

A troupe of lithe young dancers in traditional dress soon emerged from the wings. As I watched them wave the flag of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic in time to “We Are the World,” I wondered: was anyone aware of the flag’s meaning? Two horizontal bars of red, symbolizing courage and heroism, sandwiching a bar of blue, for nationhood, and, in the center, a piercing white sphere: the light of communism. Sitting in the basket of my motorbike was a faded original 1968 edition of revolutionary leader Phoumi Vongvichit’s Le Laos et la lutte victorieuse du peuple Lao contre le neo-colonialisme Americain, which I had plucked out of a pile of old magazines at a used bookshop and purchased for a few dollars that morning. The editor’s note begins, “While American neo-colonialism around the world suffers defeats ever more stinging…” Now, forty years later, the words of America’s most successful pop star filled the courtyard of the Prime Minister’s Office.

Back when I lived in Vientiane, I would have found this juxtaposition deeply unsettling. It would likely have sent me into a deep funk. Tonight, however, it seemed somehow natural. After all, in death Michael Jackson had transcended his American roots to become part of the entire world’s heritage; Laos was claiming his legacy for itself. By hosting this important event, Laos had transformed from mere victim of cluster bombs into advocate for their eradication, showing that it, too, could be a player on the world stage. As the guests filed out of the courtyard, past trees draped with twinkling blue Christmas lights, they took group photographs and embraced. A feeling of pride and triumph was in the air. Perhaps even Phoumi Vongvichit would have entertained the notion that the flag’s transition from his Marxist comrades’ wartime headquarters in the caves of Northern Laos to the Prime Minister’s just-finished courtyard was actually quite smooth.

As I pulled out of the back gate, the anthem of global solidarity was being played on repeat, again and again, over the loudspeakers and out into the darkness beyond.

___

A few days later, I had lunch with an old colleague from the NTA who had since left to work for a non-governmental organization: less prestige, perhaps, but a much better salary. After we finished our wonderful meal of nem neuang, grilled Vietnamese pork balls and rice noodles, I convinced my friend to join me for a visit to the woman whom I considered to be the purveyor of the best ice coffee in Vientiane. We turned off Samsenthai Road, just past the Culture Hall—built by the Chinese when I was living in Vientiane, and the site of the opening ceremony for the Cluster Munitions Convention meeting—and parked where we remembered her stall to be. In its place was a new, multi-storey apartment building; the coffee seller was nowhere to be found. Instead, my friend and I drove around the corner to True Coffee, the local branch of a Thai chain, and among the first international franchises in Vientiane. Tourists enjoyed the air conditioning while checking e-mail and perusing the pricy Apple computer products that were for sale. We sat down for a chat with the owner, another old friend; earlier in the year she had also brought Swensen’s and The Pizza Company franchises to Vientiane.

I ordered a Decaf Skim Iced Mocha Latté. It was tasty, but I longed for my beloved Lao iced coffee. Starbucks and its imitators were ubiquitous everywhere else in the world; did Vientiane really need them as well?

After bidding my friends goodbye, I walked over to the National Museum, just across the street from Swensen’s. I had seen the quirky, dusty exhibits—which included everything from dinosaur bones to communist machine guns—many times before. Now I simply wanted to pay my respects to this grand old building, which, I had just learned, was also threatened by the wrecking ball. Built in 1925 for use by the French Governor-General, the building had been employed by the Japanese during their brief occupation of Vientiane during World War II. But it was also here that the Lao Issara, or Free Laos, government proclaimed the nation’s independence in October 1945. After the revolution, it had served a number of Lao People’s Democratic Republic ministries before being converted into a museum.

Now, the property—along with two other important colonial-era structures, the National Library and the Ministry of Information and Culture—had evidently been sold to a wealthy developer who planned to demolish the museum and build an office and retail complex in its place. As for the contents of the museum, they would be relocated to a modern facility outside of town, thereby ensuring that no one would ever see them. I paced around the stately grounds, overgrown with weeds, and contemplated the potential loss of another piece of Vientiane’s heritage. I could understand the government’s weariness of calls from Westerners to preserve old French edifices; had they not done enough heritage protection in Luang Prabang under the relentless needling of UNESCO? Nevertheless, these buildings form an integral part of Lao history, and it is hard to see what motivation there is for their destruction, other than short-term monetary gain by specific individuals. It is always cheaper to knock down a building than to save it (although the experience of Luang Prabang shows that there is plenty of money to be made by retrofitting colonial structures).

By the time this edition goes to print, I fear that the National Museum will have fallen victim to the inexorable drive to make Vientiane a modern metropolis: the dream, evidently shared by the Lao leadership and many of its citizens, of creating a normal city at last. Tourism may be on the rise, but if this effort ever succeeds, I wonder if anyone will still want to visit.

___

When I handed over the 5,000-kip note in exchange for a laminated photograph of Prince Pethsarath, early prime minister of Laos and a member of the royal family—and an important voice for the preservation of traditional Lao art and culture—a fellow cu

stomer murmured his approval.

“Ah, Pethsarath, good choice!” he said, a broad smile on his middle-aged face.

“Oh yes?” I asked, examining the mystical drawings and pali script that surrounded the Prince’s likeness. “What’s so great about him?”

“He was a very holy man, sacred—very good luck for you!”

When I lived in Vientiane, images of Pethsarath and other pre-revolutionary celebrities had been common enough, but mostly inside homes. They had been recommended to me as good-luck charms in hushed tones, if at all; now they were being churned out of a portable printer on the banks of the Mekong River. A few hundred feet away stood the latest addition to Vientiane’s array of monuments, a towering statue of Chao Anouvong, the ruler of the Lan Xang Kingdom from 1805 until 1828. Anouvong’s reign was no grand success: after launching an attack on the Siamese in 1826, he was captured during their fierce response, which resulted in the destruction of Vientiane and Anouvong’s death in captivity in Bangkok.

Nevertheless, the current government in Laos had decided to resurrect Anouvong, completing the ten-ton likeness in just four months, in time for the 450th anniversary celebration. Deputy Prime Minister Somsavat Lengsavath—whom I remember meeting back when he was merely foreign minister, in a chance encounter in the men’s room at the Lane Xang Hotel—had been put in charge of the festivities. According to the Vientiane Times, at the recent unveiling ceremony, he had praised the former king’s “unwavering love for his country and how he devoted his life to keeping the Siamese at bay. Even though the king was imprisoned and tortured, Mr. Somsavat said, he was undaunted in showing his love for his country and fought without surrender.” The provocative placement of the statue on the banks of the Mekong, directly facing the Thai, Anouvong’s hand outstretched toward them, reinforced the message: we may have lost, but we have not forgotten.

Another Quiet American

Another Quiet American